Have you seen the recent advertisements from Nationwide UK with fabulous poet, Jo Bell, telling the story of Alfred and Elizabeth Idle? Working with Nationwide, I researched the full history of the former home of Alfred and Elizabeth Idle – No.29 Morrison Street – where Alfred took out the first mortgage with Nationwide in 1884.

The history was compiled to tell the story of the first mortgage, but also because they are offering a chance to win an illustrated house history (researched by me!) If you’re interested – more details can be found here (with full terms and conditions): Competition – Does your home have a secret history?

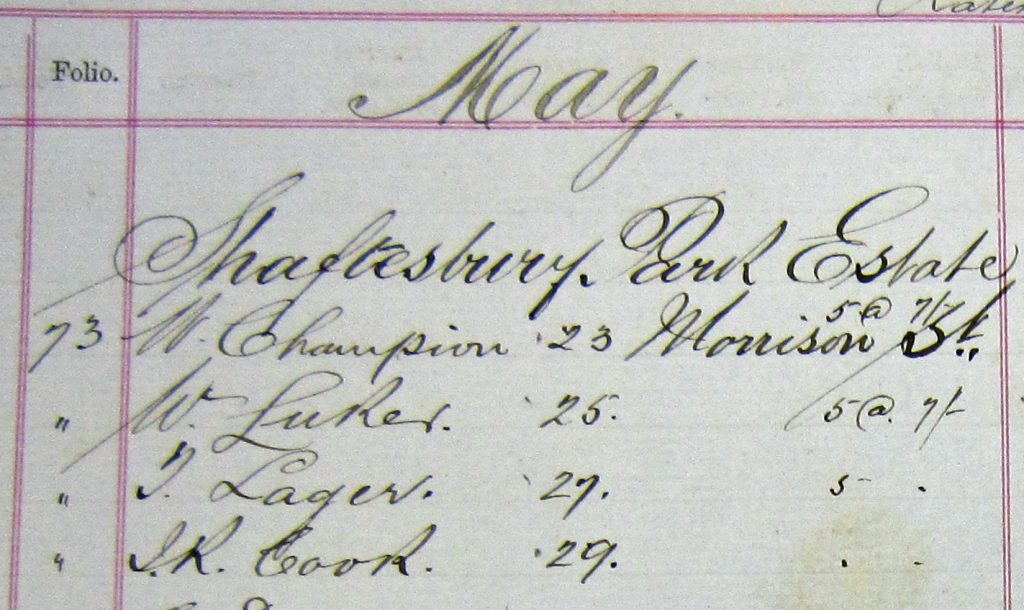

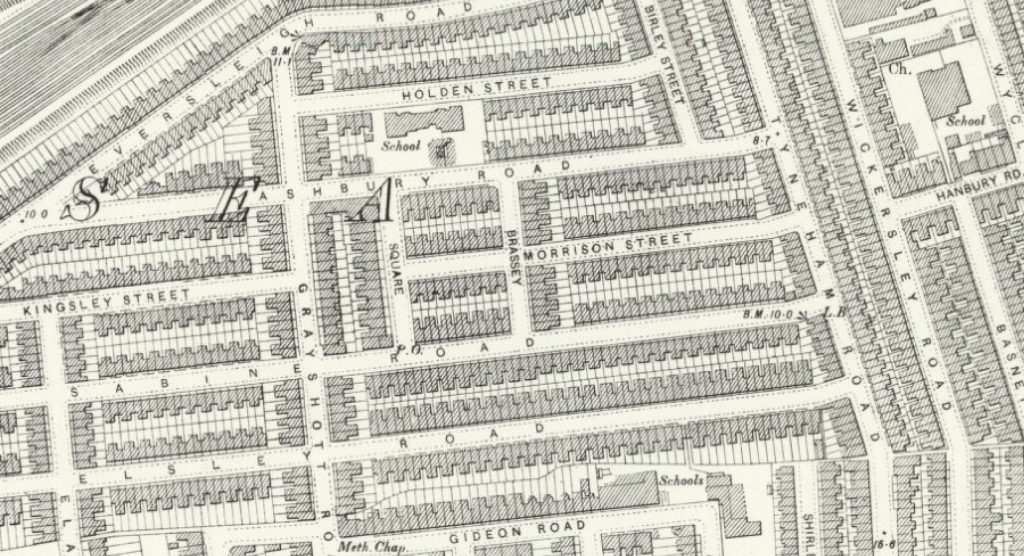

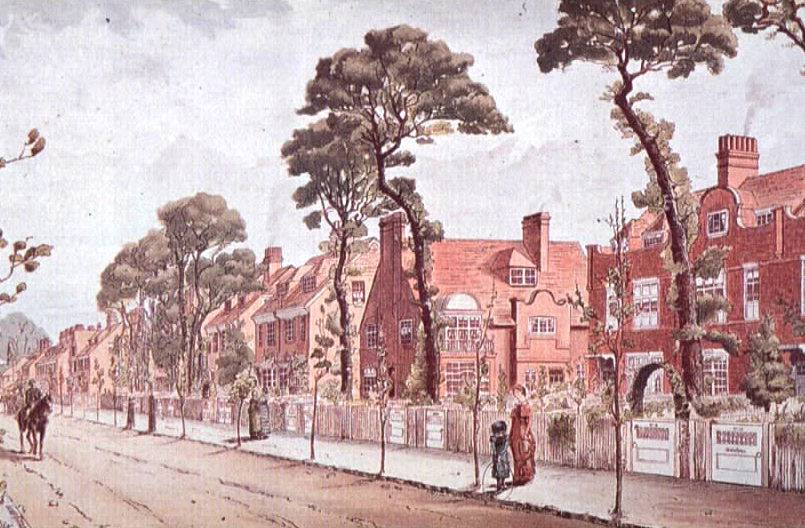

A short history of the house appears on the Nationwide website, but I wanted to reveal a little more of the story from when the house was first completed in 1876. Although the first mortgage was taken out by Alfred Idle, rent books reveal the very first occupant of the house was a Mr J.R. Cook in May 1876.

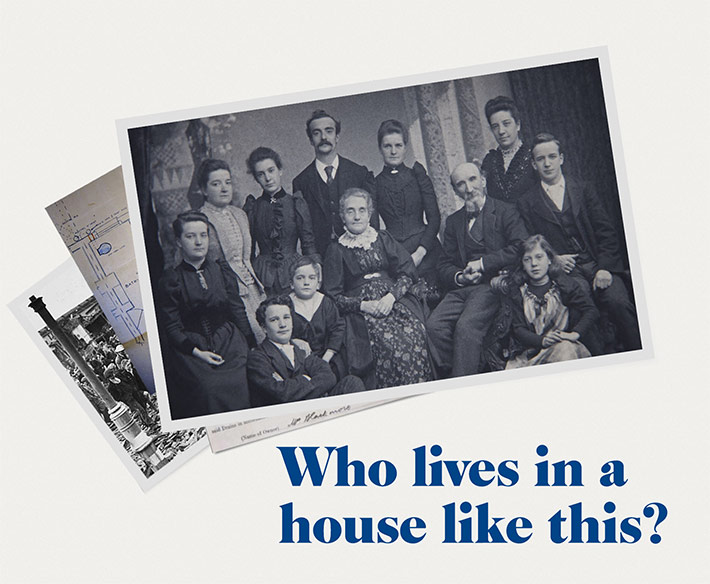

However, within a few months Alfred Owen Idle, librarian assistant at Mudie’s Library, moved into the house with his wife Elizabeth and nine children. Alfred Idle first bought the house from the ‘Artizans’, Labourers’, & General Dwelling Company Ltd’, for £210 in 1876.

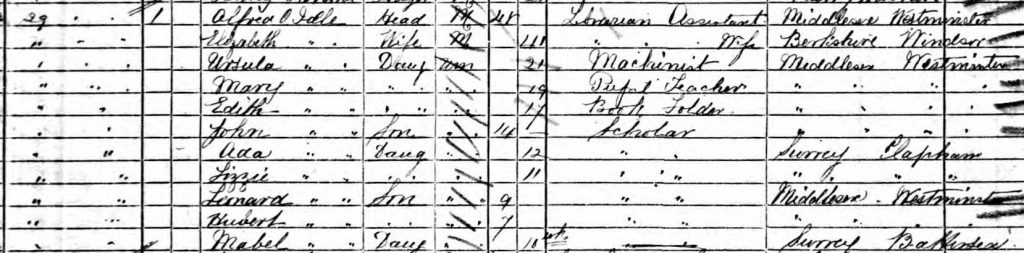

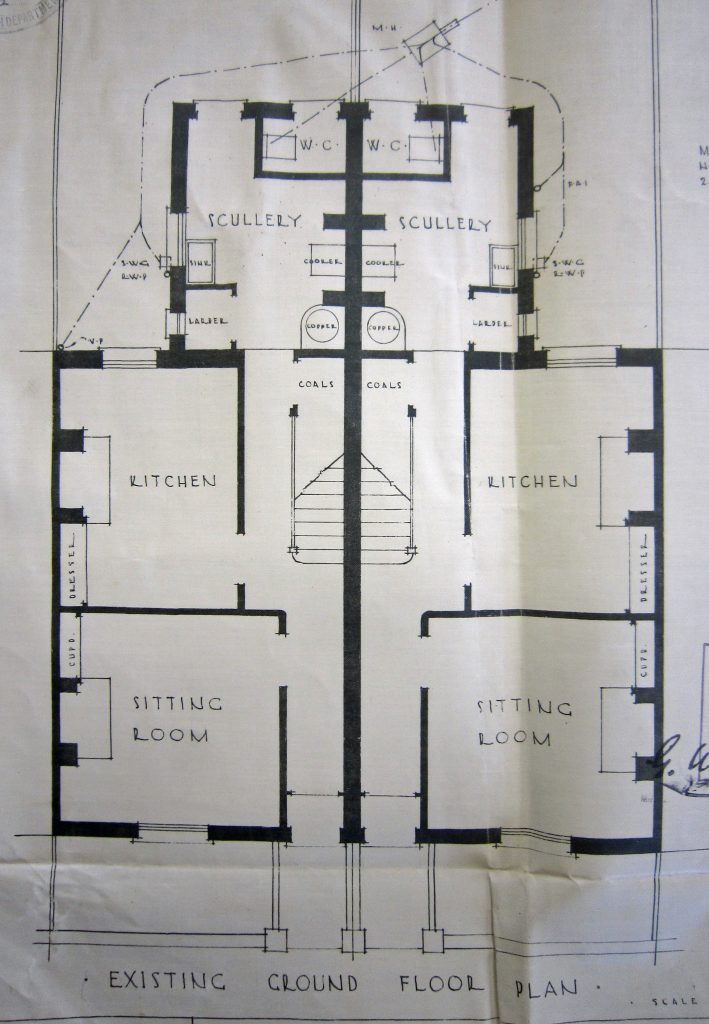

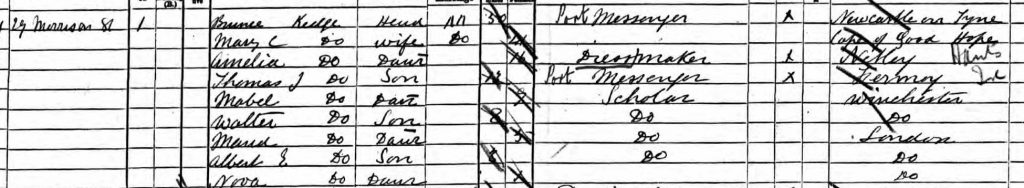

A few years later, when the census was taken in 1881, a full picture of the Idle family is revealed, with Alfred and Elizabeth and their nine children, living in a house with three bedrooms, a parlour, kitchen, scullery, and an outside toilet.

In 1884, Alfred Idle acquired a new mortgage for No.29 Morrison Street from the Southern Co-operative Permanent Building Society, now part of today’s Nationwide Building Society. At this time the house was valued at £220 and Alfred was advanced £120 from the building society, with repayments of 6 shillings and 1 penny a week for ten years. Mr Alfred Owen Idle was the first person to take out a mortgage with Nationwide. However, after acquiring the mortgage, he moved from Morrison Street and by 1887 the new occupants were the Kedge family.

A few years later, the 1891 census reveals head of the house, Bruce Kedge, a ‘porter – messenger’, along with his wife, Mary and their seven children, aged between one and sixteen. However, this is a classic example of needing to dig a little further when researching the history of a house, as it is revealed that prior to becoming a messenger, Bruce Kedge was a Sergeant of the Rifle Brigade. He had first enlisted in the 1st Battalion Rifle Brigade when he was 20 years old, and served in many places across the country, including Winchester, Woolwich, and Dover, as well as in Canada for eight years, in 1861-1869.

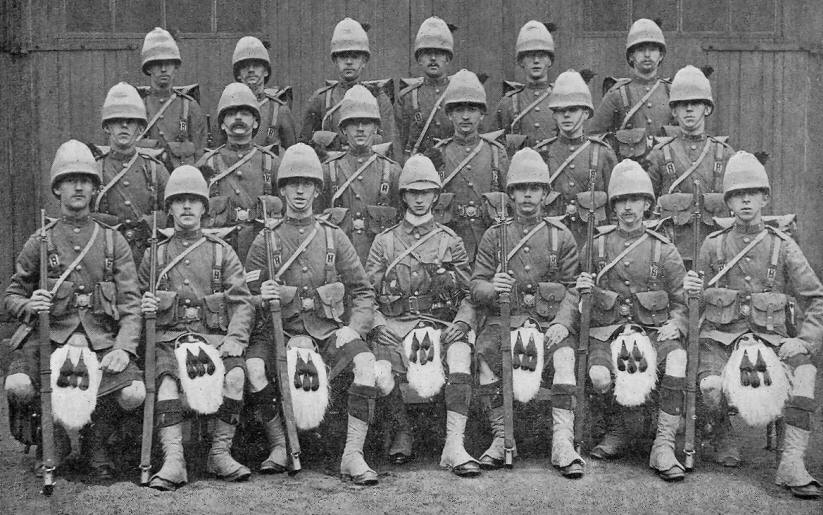

Three of Bruce and Mary’s sons followed Bruce into the military, with their eldest son, William enlisting in the Scottish Highlanders (The Black Watch) as a musician, when only 16 years old, in 1890. William Kedge went on to serve in the Second Boer War, in 1901-1902, receiving a Queen’s Medal with four clasps.

Another of Bruce and Mary’s sons, Thomas, enlisted in the Rifle Brigade when only 15 years old, in 1892, but like his brother William was serving as a musician. He gained the rank of Corporal in 1898, but in 1901 he reverted to Private due to misconduct. The details of his ‘misconduct’ are not certain, but it is clear it did not affect his service to the military as he went on to serve in Hong Kong and Singapore, and he served in The Boer War twice between 1899 and 1902, when he received the Queen’s Medal and King’s Medal. Thomas Kedge transferred to The Black Watch, but by 1905 he had been discharged. He served again in 1906-1907 but left the army again by June 1907. However, at the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Thomas Kedge re-enlisted (nine days after the declaration of war) and despite being sent to France in August 1914, he returned to England only 18 days later and spent the remainder of the war years stationed in England.

The last of Bruce and Mary’s sons to serve in the army was Albert, who enlisted in the Royal Highlanders when he was 19 years old, in 1906. Albert only served for eight years, and was discharged in March 1914. Like his brother Thomas, he re-enlisted at the outbreak of the First World War and served throughout the war. By 1918 he was serving with The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) as Acting Company Sergeant Major.

Meanwhile, back at No.29 Morrison Street, Bruce and Mary Kedge continued as the occupants throughout the final years of the 19th century through to the early 1900s. Alfred Owen Idle continued as the leaseholder (which later passed to his children after his death in 1918), while the Kedge family continued to rent the house. Bruce Kedge passed away on 14 February 1911, while Mary Kedge continued in Morrison Street until she passed away in January 1915.

Prior to this time, Bruce and Mary’s second eldest daughter, Mabel, had married motor bus driver, Edward John Gaitt, in the spring of 1902. The young couple spent the first years of their marriage living with Mabel’s parents in Morrison Street, but they later moved to Islington and Fulham. In 1903, Edward Gaitt was recorded as a ‘bus conductor’ but by 1904 he had become a bus driver. This is a significant profession at this time when horses were still the dominant power for transport, but Edward Gaitt was one of the early drivers of motorised buses in London.

After the death of her mother, Mabel and her husband Edward moved back to No.29 Morrison Street. Earlier records reveal Edward Gaitt’s father, also named Edward, was a ‘firework artist’ and ‘pyrotechnical artist’, a most unusual profession.

After the death of her mother, Mabel and her husband Edward moved back to No.29 Morrison Street. Earlier records reveal Edward Gaitt’s father, also named Edward, was a ‘firework artist’ and ‘pyrotechnical artist’, a most unusual profession.

As a motor bus driver, Edward Gaitt was at the forefront of London transport and its transformation during the early 20th century. The motorised bus first came to the streets of London during the early 1900s and by 1908 there were over 1100 motor buses. The last horse bus service ran in London in October 1911. It is most likely Edward John Gaitt would have driven the LGOC B-type bus, introduced in 1910, which became famous for its use during the First World War.

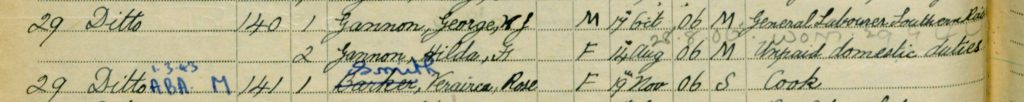

By the end of the First World War, Edward and Mabel were at No.29 Morrison Street with their eight children. They continued at the house throughout the 1920s and 30s, but by March 1937 they had moved to a slightly larger house nearby and the new occupants in Morrison Street were George and Hilda Gannon. When the 1939 Register was taken in the first month of the Second World War, it revealed George Gannon was 32 years old and working as a general labourer for Southern Rail, and Hilda, also 32 years old, was working in ‘unpaid domestic duties’ (a ‘house wife’). The couple also had a lodger, a cook, 32 years old, Veronica Rose Barker, who later went to serve with the Women’s Royal Naval Service – the Wrens.

The risk of bombing in Morrison Street was very real (with close proximity to the River Thames, Clapham Junction station, and Battersea Power Station!) and the area suffered many attacks during the war. Morrison Street received a direct hit by a V1 rocket on the morning of 17 July 1944, which completely destroyed Nos.37-49 Morrison Street (just a few doors down from No.29).

By the end of the war, George and Hilda Gannon were no longer at the house and they were renting it to a new family, George and Daisy Farrall. George and Daisy lived at No.29 for a little over ten years, but records reveal the house was then sold in 1958. Drainage plans reveal that it was at this time, over 80 years after the house was first built, that a bathroom was fitted inside the house.

This typical London house in the streets of Battersea has certainly seen a lot of history over the years. With its connection to Nationwide and the first mortgage granted to Alfred Idle in 1884, as well as the military connections of the Kedge family, and several other stories of owners and occupants who have all played their part in the history of London, but also the history of this house.

Don’t forget, you can enter the Nationwide house history competition here – Nationwide: Does your home have a secret history?

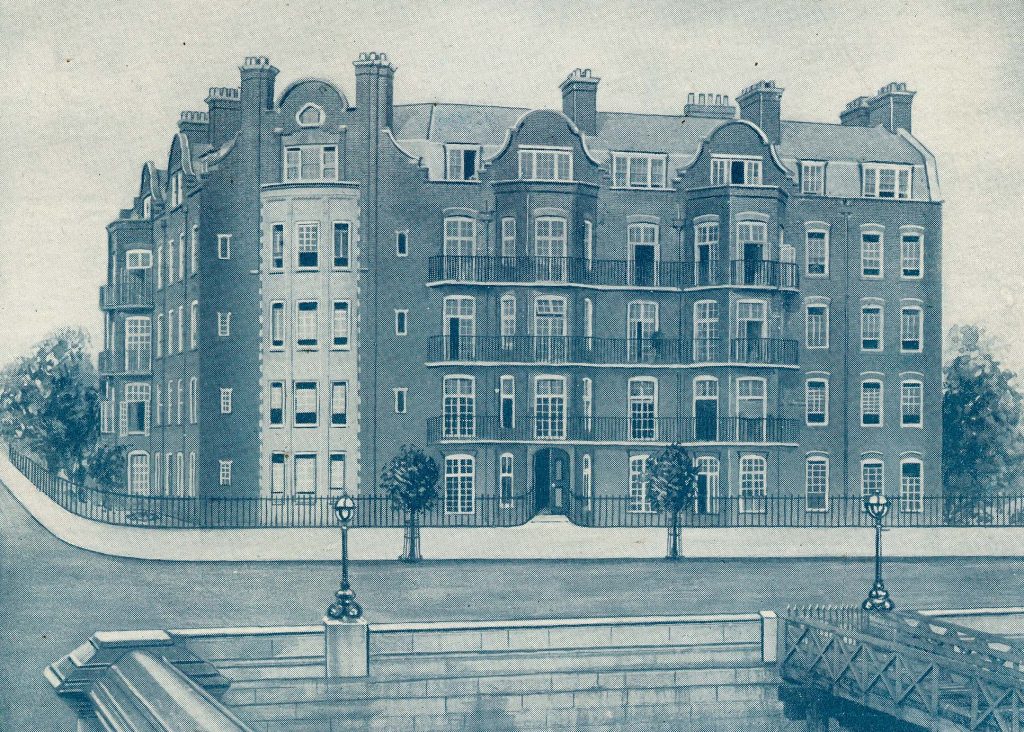

![More's Garden, Chelsea [image courtesy of Chestertons]](http://www.house-historian.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Mores-Garden_Cheyne-Walk_External-no-traffic_Chesterton-1024x681.jpg)

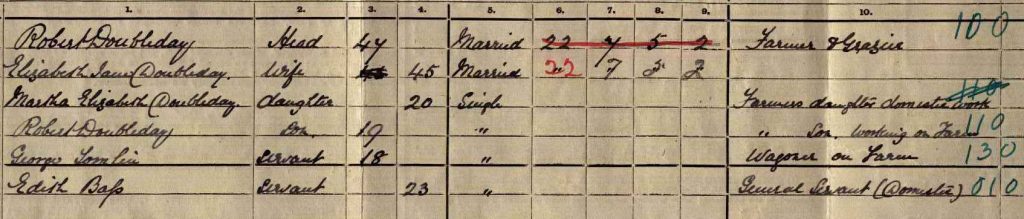

![More's Garde sales particulars, 1903 [image courtesy of Kensington and Chelsea archives]](http://www.house-historian.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Mores-Garden-sales-particulars-1903_page-1_crop-717x1024.jpg)

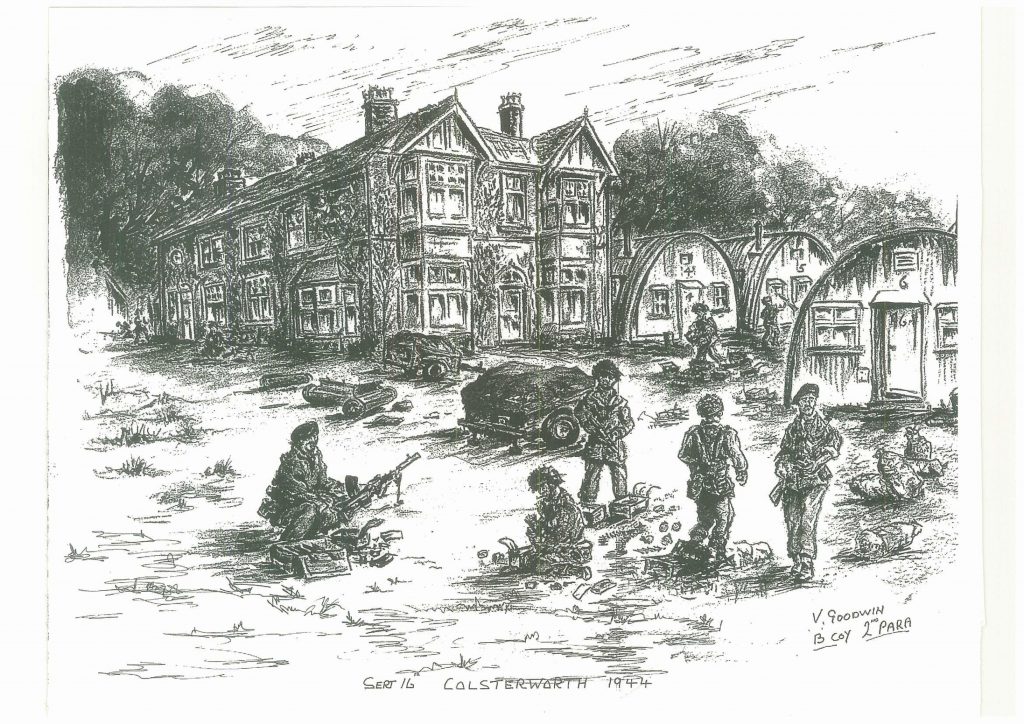

![Millfield, Colsterworth [image courtesy of Chestertons]](http://www.house-historian.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Millfield-84194-ph27-1024x680.jpg)

![Mrs Saker (left) in The Masqueraders, 1894 [image courtesy of https://footlightnotes.wordpress.com/tag/irene-vanbrugh/]](http://www.house-historian.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Mrs-Edward-Saker_left_The-Masqueraders_1894.jpg)