I have been a little quiet on my blog in the last few months as the second half of 2016 was packed with exciting projects, which made blogging my adventures a little tricky! However, one of the projects in west London has inspired this first of my blog posts for 2017!

Late last year, I was working with the Bedford Park Residents Association on a new house history project, engaging with the residents and local people in promoting the social history of this unique enclave in west London. For more details, you can read the announcement here – BPRA Launch House History Initiative. To launch the project, I spoke at an event in Chiswick talking about the fascinating historic stories you can uncover by researching the history of houses. This included a fabulous story about the residents of a house in Bath Road that I discovered in preparing for my talk at the event.

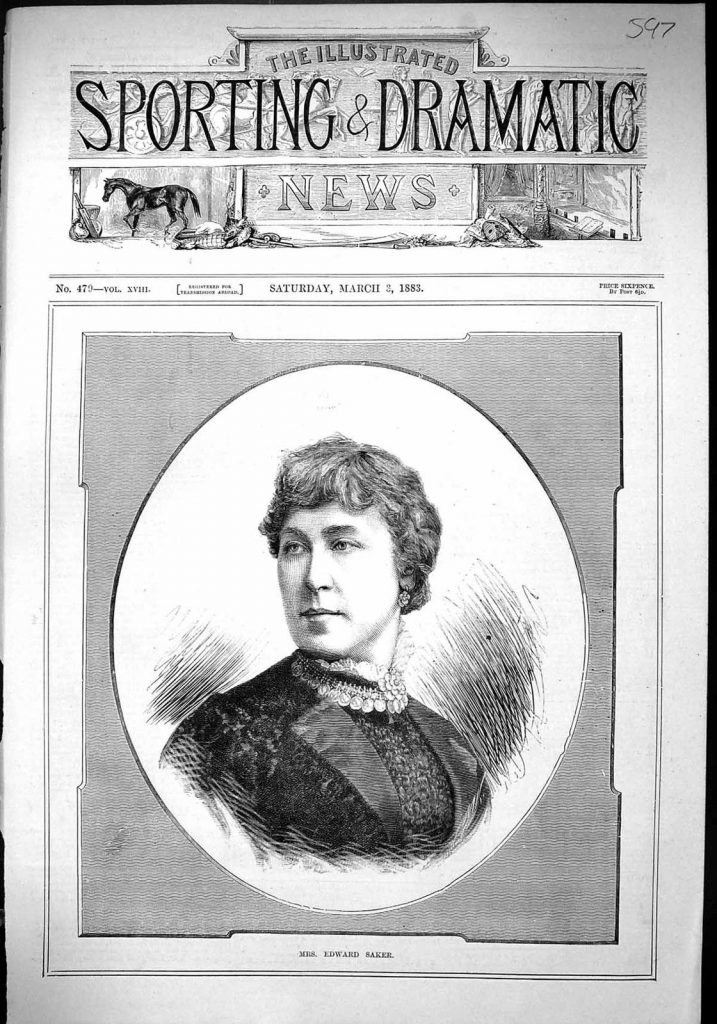

In looking through the 1891 census for Bath Road, which runs along the boundary of Bedford Park, I found the widowed, Marie Saker, recorded as an actress. She was living in the house with her grandmother and four children, along with a governess and two live-in servants. Her eldest son, George, was a student at the Royal Academy of Music, while her middle son, only thirteen years old, was recorded as an ‘actor’. I admit, I had not heard of Marie Saker, but I was intrigued by the reference to her being an actress and began to delve a bit further.

![Mrs Saker (left) in The Masqueraders, 1894 [image courtesy of https://footlightnotes.wordpress.com/tag/irene-vanbrugh/]](http://www.house-historian.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Mrs-Edward-Saker_left_The-Masqueraders_1894.jpg)

In an unusual move (or perhaps more likely forced due to financial need) Marie Saker continued the management of the Alexandra Theatre in the footsteps of her husband. She continued to manage the theatre for several years, certainly an unusual position for a woman in those times, but by 1888 she had moved on and by 1891 we find her living in Bedford Park in Chiswick.

I also found a fabulous piece of theatrical history previously owned by Mrs Edward Saker, which has survived and is now held in The National Archives [Ref: 920 MD 411]. It is the former autograph book of Marie Saker. It is inscribed with a note “This book belonged to Mrs. Saker of Liverpool and came into my possession in February 1895”; signed by Edgar Pemberton [playwright and theatrical historian]. The book is a ‘Who’s Who’ of the late 19th century theatre and includes notes and signatures from many famous names, including Oscar Wilde, Sarah Bernhardt, Ellen Terry, Henry Irving, and former Prime Minister, William Gladstone.

In delving further into the story of Marie Saker and her children, I found a very sad turn of events with two of her sons dying during the First World War.

Marie and Edward’s youngest son, Frank, had first joined the military in 1901 so was one of the first to be fighting at the outbreak of the war. He was promoted to Captain in September 1914, but died the following month, on 30 October, on Flanders Fields.

Edward and Marie’s second son, Richard (who had been recorded as an actor in 1891) also joined the military early and served with distinction during the Boer War in South Africa and was awarded the Queen’s Medal with five clasps. At the outbreak of the First World War he was attached to the Australian Infantry as Major and took part in the landings at Gallipoli in 1915. He was wounded several times on the landing, but continued to fight until he was fatally wounded and died on 20 April 1915.

This is just one part of the life of one house and just goes to show the extraordinary stories that can be discovered by researching the history of a house!

Note: if you live in Chiswick and want to know more about the Bedford Park House History Initiative, get in touch with the BPRA – here.

You can also hear some more about the project by watching some recent films made by The Chiswick Calendar – Discover the history of your house with Melanie Backe-Hansen